Symmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex

The Symmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex (STNR) has two automatic movement patterns resulting from flexion and extension of the head. With this reflex, when the head moves, the upper and lower body parts simultaneously engage in opposite movements. When an infant’s head extends, the upper body also extends while the knees bend and the infant’s bottom sinks down onto the ankles. When the head is flexed, the arms bend while the legs extend—causing the lower torso to raise up. Because the STNR helps the infant to get off the ground and into a 4-point position, it is a necessary precursor to hands-and-knees crawling.

The Symmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex (STNR) has two automatic movement patterns resulting from flexion and extension of the head. With this reflex, when the head moves, the upper and lower body parts simultaneously engage in opposite movements. When an infant’s head extends, the upper body also extends while the knees bend and the infant’s bottom sinks down onto the ankles. When the head is flexed, the arms bend while the legs extend—causing the lower torso to raise up. Because the STNR helps the infant to get off the ground and into a 4-point position, it is a necessary precursor to hands-and-knees crawling.

STNR generally emerges between 6 and 9 months of age, and ideally integrates by 12 months. It is one of the most important reflexes for developing optimal coordination, motor skills, attention, and academic learning. If the STNR is not integrated, children may roll, bottom scoot, or make other compensatory movements to get around. Others will skip these movements entirely and remain sitting until standing and walking become possible—though there may be challenges in those areas as well since STNR helps to align the spine in preparation for standing upright.

As with the Asymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex, the STNR is also involved in visual tracking and convergence: it assists infants in lifting and controlling the head for both near and far distance focusing.

A retained STNR is a main contributor to poor academic functioning. This is because up and down head movements are inappropriately linked to arm and leg movements, making tasks such as reading and writing effortful and difficult. An unintegrated STNR can also interfere with proper posture and the ability to sit comfortably. When seated at a desk, individuals may slump in the chair, use a hand to prop the head up, wrap legs around the chair or table legs, or stretch legs out in front to compensate.

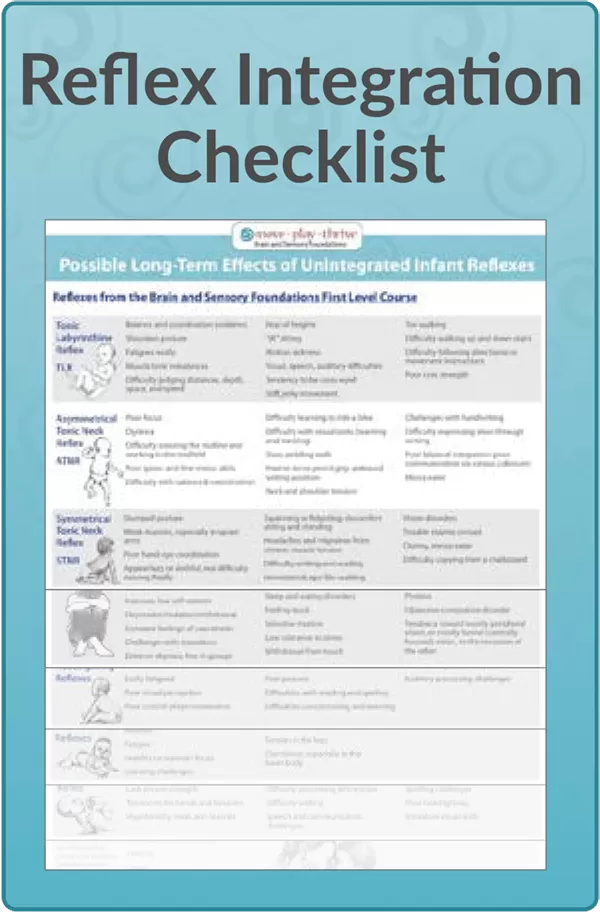

Possible Long-Term Effects of an Unintegrated Symmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex:

- ADHD

- Squirming or fidgeting; poor posture, slouching

- Weak arm muscles

- Headaches from muscle tension

- Reading and writing challenges

- Difficulty sitting still

- Difficulty copying from a blackboard

- Ape-like walking

- Vision disorders

- Poor eye-hand coordination

- Trouble staying on task

- Clumsy, messy eater

- Amphibian Reflex

- Asymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex

- Birth and Bonding

- Crawling Reflexes

- Crossed Extensor Reflex

- Facial-Oral Reflexes

- Fear Paralysis Reflex

- Feet Reflexes—Plantar & Babkinski

- Foot Tendon Guard

- Hand Reflexes—Grasp, Palmar, and Babkin

- Headrighting Reflexes

- Infant Torticollis

- Landau Reflex

- Moro Reflex

- Parachute Reflex

- Pull-to-Sit Reflex

- Spinal Galant Reflex

- Spinal Perez Reflex

- Symmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex

- Tonic Labyrinthine Reflex

Sources

Blomberg, H. (2015). The rhythmic movement method: A revolutionary approach to improved health and well-being. Lulu.com.

Bly, L. (2011). Components of typical and atypical motor development. Neuro-Developmental Treatment Association, Incorporated.

Domingo-Sanz, V. A. (2024). Persistence of primitive reflexes associated with asymmetries in fixation and ocular motility values. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 17(2).

Goddard Blythe, S. (2023). Reflexes, movement, learning & behavior. Analysing and unblocking neuro-motor immaturity. Hawthorn Press.

Goddard Blythe, S. (2014). Neuromotor immaturity in children and adults: The INPP screening test for clinicians and health practitioners. John Wiley & Sons.

Masgutova, S. (2007). Integration of infant dynamic and postural reflex patterns: Neuro-sensory-motor and reflex integration method [Training manual].

Taylor, M., Chapman, E., & Houghton, S. (2004). Primitive reflexes and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Developmental origins of classroom dysfunction. International Journal of Special Education, 19(1), 23-37.